Where Have All the Bug Splats Gone?

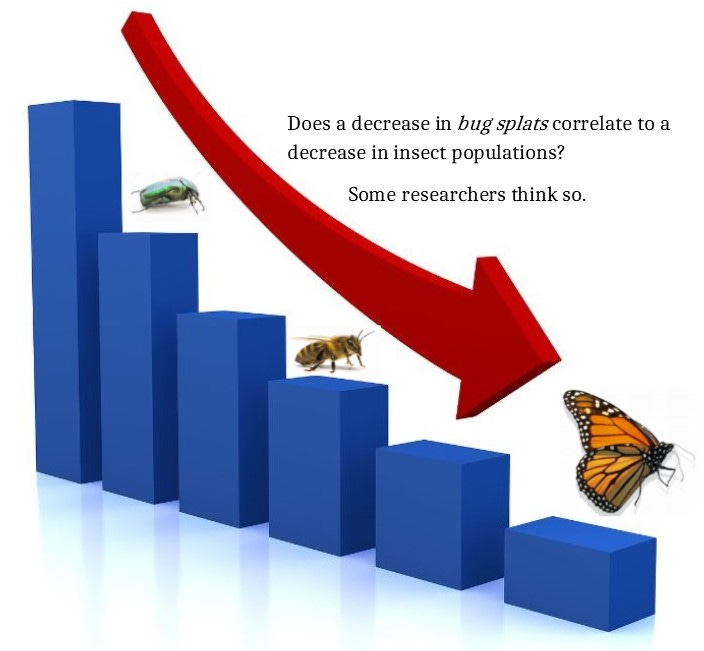

Who remembers going for summer drives and coming home with a windshield full of bug splats? That hasn't happened in a long time, huh. So, what happened to all the bugs?

Believe it or not, I'm not the first person to ponder this question. During my research, I found several articles and even some studies concerning the worldwide decrease in bug/vehicle encounters. The trend has even earned a name.

Entomologists call it the windshield or windscreen phenomenon, hypothesizing that the observation of fewer dead insects on the windshields of people's cars is due to a global decline in insect populations.

Are There Fewer Bugs, or Is It Just a Coincidence?

The first step in answering this question is to count the bugs.

In the 1980s, the Krefeld Entomological Society began gathering data by tracking the insect abundance at more than 100 nature reserves across Germany. In 2013, they reported an alarming discovery. At one site, the total mass of their catch had dropped nearly 80 percent since 1989. To double-check their finding, they set up identical traps again in 2014 — same result. Investigations across more than a dozen additional sites showed that the trend wasn't limited to one area.

Ongoing annual monitoring indicates that insect populations across Germany are continuing their downward spiral.

Some scientists question the notion of an insect apocalypse based on this German study. However, others are more cautious. They need information on how insect numbers are faring across the world.

We are all aware of the detrimental effects of habitat loss, overuse of pesticides, global warming, and pollution on insect species. In the U.S., data has tracked the dwindling populations of Monarch butterflies, honey bees, native bees, and fireflies. However, moths, hoverflies, beetles, and countless other insects have not been studied as well. Have their numbers declined as well?

The Krefeld data says yes. Hoverflies declined from 17,291 in 1989 to 2737 in 2014. Observations by citizen scientists worldwide confirm that not only insects but birds and other wildlife populations are dwindling as well.

To link the above data to what drivers are seeing, surveys were conducted by the Kent Wildlife Trust. They followed more than 650 car trips taken across the British county of Kent in the summer of 2019, recording the number of dead bugs found on their car's license plate. They compared these numbers to the results of a similar survey from 2004 and found that the average splattered insect count had dropped by 50 percent.

Of course, this was a survey instead of a carefully conducted scientific study, and the bug splats were on the flatter front portion of the car (license plate), but the results do show a disturbing trend. To counter the folks who blame the lack of bug strikes on the more aerodynamic designs of modern cars, the Kent Wildlife Trust researchers included drivers with classic cars in their survey. Even with the boxier, less aerodynamic vehicles, their findings still suggest that the change over 15 years came from the environment — not car designs.

The Nay-sayers

John Rawlins, head of invertebrate zoology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, disagrees with the theory stating the insect population has radically decreased. Instead, he believes the windshield phenomenon is more complicated, and additional factors must be considered to get the whole story. He concurs that the diversity of bugs meeting an untimely end has diminished, but he says the density or number of splats has remained the same. It looks like fewer splats because we're hitting smaller bugs. The larger insects no longer hang out near the roadway since the shoulders are mowed more extensively. Bush hogs with boom attachments cut down roadside vegetation before it flowers. Roadside ditches and slopes no longer serve as insect breeding areas. So, the big bugs find somewhere else to do their business.

Rawlins is also a proponent of the premise that aerodynamic changes in car design account for fewer splats. The flat-fronted cars of yesteryear have been replaced with sleek, slick automobiles. "The bug gets into the laminar airflow and goes across the vehicle. It never has contact with the vehicle."

Manu Saunders doesn't buy into the windscreen phenomenon either. He says the reduced number of bug splats is just an anecdote, not scientific evidence. "Traffic volume, time of day, season, the width of the road corridor, land use on either side of the road, paved vs. unpaved, insect sex or life history traits, baseline insect populations, and pollution can all influence the observed effect a road has on an insect. Most studies that have tested the effects of roads on insects have found variation depending on the environmental context."

Saunders adds another reason for fewer bug splats: narrow two-lane roads have been replaced with four-lanes and interstates. As a result, insects must fly farther and farther from vegetation to hit a windshield.

Are We Headed For an Insect Apocalypse?

The debate continues. We know insect populations are declining, but does that mean they will eventually all die off? Climate change, human land use, overuse of pesticides, and the continued introduction of invasive species continue driving changes in insect population sizes and biodiversity. Yet, do these events signal a doomsday for bugs?

Not in the near future. I agree with the Entomological Society of America's Global Insect Biodiversity FAQs, which states, "Even though many insect species are seriously threatened, projections of a looming mass extinction of insects are premature."

I remain a half-glass-full optimist and believe many people in this world care about Mother Earth and all Her lovely creatures. We won't sit back and let close-minded idiots hold back progress.

The reduction of bug splats should serve as a wake-up call to correct humanity's past mistakes and create a brighter future for invertebrates.

Bug splatter isn't what it used to be and may never return. Whether the windshield phenomenon is caused by more aerodynamic cars, wider highways, or fewer bugs, it's a fact we can't ignore. However, we can do our part to stop the declining insect populations just by following these four steps.

Restore the native flora destroyed by agricultural, industrial, and residential development with landscapes filled with flowers, trees, shrubs, and other plants the insects need. In other words, replace useless grass and non-native ornamentals in yards and other green spaces with a diverse selection of indigenous plants.

Reduce or stop the use of pesticides.

Get rid of non-native and invasive species.

Reduce your carbon footprint. Climate change represents multiple threats to insect life, such as shifting life cycles and geographic ranges, stressing the plants insects feed on, and increasing the likelihood of droughts and fires.

How about you? What do you think? Please comment below to express your thoughts. Are we headed to an insect apocalypse?

If you have the time, please consider recommending Let’s Get Our Hands Dirty to others on Substack and other social media platforms. I’d greatly appreciate it.

Thanks!

Greta

Two Splatologists from The Verge went on a cross-country adventure to research the windshield phenomenon. Their mission was to document and catalog as many bug splats as they could find along the way.